Chris Schreiber

Discover how structured cyber drills can strengthen collaboration and improve incident response in higher education, ensuring a robust cybersecurity posture.

With the global average cost of cyberattacks reach record highs each year, higher education institutions face unprecedented cybersecurity challenges. While universities house valuable research data and sensitive student information, coordinating across departments for effective incident response can be challenging. Ineffective collaboration between information security teams and other key university departments is a significant vulnerability that higher education cybersecurity leaders must address.

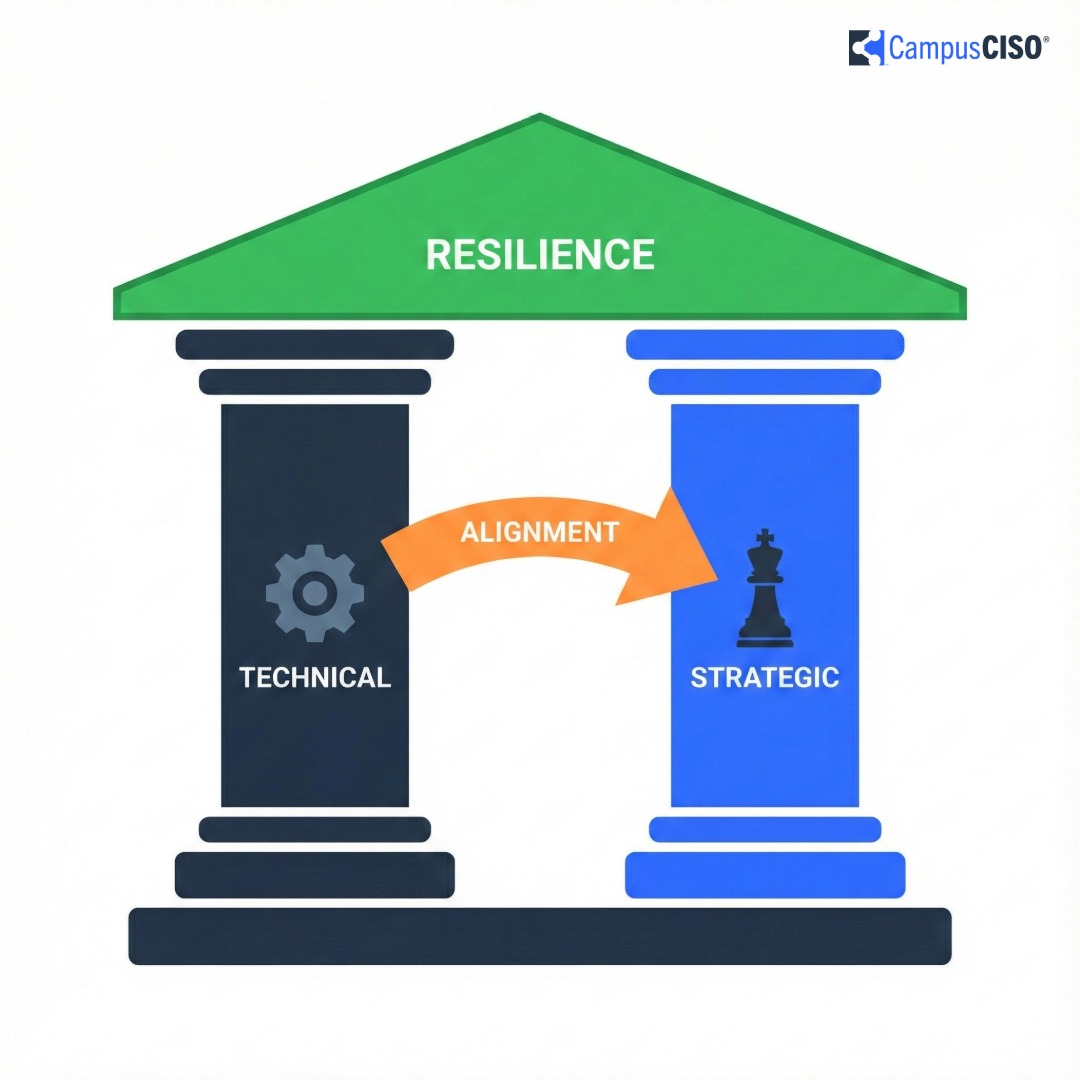

A cyber drill, sometimes referred to as a Tabletop Exercise or TTX, is a structured simulation of potential cyber incidents designed to help institutions practice, evaluate, and refine their response strategies. By placing participants in realistic scenarios, drills highlight the importance of collaboration among technical and non-technical stakeholders, strengthening overall institutional resilience.

Cyber incidents at universities don’t stay contained within IT departments. They ripple throughout the entire institution, and may need input from marketing, legal, academic leadership, law enforcement, student affairs, registrar offices, and even housing services. These non-technical stakeholders aren’t always engaged in incident response preparedness, leaving institutions vulnerable to confusion and delayed action when incidents occur.

Recent EDUCAUSE research highlights that decentralized IT governance in higher education contributes to inconsistent cybersecurity practices, amplifying vulnerabilities across campus (https://library.educause.edu/resources/2022/10/2023-top-10-it-issues). The solution lies in implementing regular, structured cyber drills that bridge these departmental gaps.

Cyber drills transform abstract policies into concrete, relatable scenarios. Rather than relying solely on documentation outlining roles and responsibilities, these exercises engage participants through role-playing that reflects realistic incidents. For instance, a simulated ransomware attack affecting student records helps registrar and student affairs teams visualize their responsibilities during such an event.

Effective cyber drill programs in university settings should include two complementary levels, starting with tabletop exercises (TTXs) for IT professionals. These drills bring together IT personnel from across campus, including network operations, security teams, helpdesk staff, and decentralized IT groups. Participants navigate realistic scenarios, such as ransomware attacks, compromised user accounts, or data breaches affecting sensitive research, and focus on technical readiness.

These exercises examine key areas, including incident detection capabilities, access to critical log data and forensic tools, communication flows within IT teams, and clarity of incident command structures. Participants identify process gaps, verify tools and procedures, and complete follow-up actions to correct any gaps.

The second tier consists of strategic exercises designed for university executives and senior leaders from departments like academic affairs, communications, legal, student services, and finance. These exercises emphasize the institutional impact of cyber incidents, allowing participants to practice decision-making and crisis communication in a controlled, non-crisis setting.

Through these strategic exercises, leaders gain firsthand insights into the university’s cybersecurity preparedness, ask clarifying questions, and identify assumptions and decisions requiring their direct input. The scenarios encourage discussions about reputational risks, regulatory requirements, and operational continuity, reinforcing the need for unified coordination during actual incidents.

Universities should establish quantifiable metrics to show the effectiveness and return on investment (ROI) of their cyber drill programs. Metrics to consider can be based on tracking participation and outcomes.

The optimal frequency for cyber drills depends on the audience and the maturity of the institution’s cybersecurity program.

For senior leadership, annual exercises reinforce familiarity with roles and support institutional awareness. Institutions just beginning structured cyber drill programs may benefit from multiple leadership exercises in their first year to identify gaps and show improvement.

Technical teams should have quarterly drills to practice and reinforce critical response skills. Institutions can hold more comprehensive exercises facilitated by outside experts annually to offer valuable external perspectives, challenge internal assumptions, and test the institution’s security posture.

As cybersecurity programs mature, universities can reduce the frequency of simpler technical drills. Institutions can challenge capabilities and maintain readiness against threats by organizing fewer, but more sophisticated, multi-layered exercises.

A key challenge in implementing cyber drill programs is securing the support and participation of non-IT leaders. Senior leaders may be difficult to engage with because of limited time and their perception of cybersecurity as an IT matter. Success starts with strong executive sponsorship, even at the board level, so that institutional culture shifts to view cyber drills as essential rather than optional.

Drills should be well-organized. The facilitator should take care to stick to the planned timetable to show respect for participants’ busy schedules. Hiring external cybersecurity experts to manage drills can enhance perceived legitimacy and engagement. Using outside experts to lead drills boosts stakeholder engagement, as an external perspective helps mitigate internal biases.

One university we work with leveraged the emergency management leader from the campus police department to coordinate a cyber drill. Rather than treating it as an isolated IT exercise, the institution integrated cybersecurity preparedness into its broader emergency management framework. Participants included IT and cybersecurity teams, campus police, facilities management, and communications staff.

The drill underscored how cyber incidents can be as disruptive as traditional emergencies, like severe weather or physical security threats. Police and facilities personnel clarified their roles in campus safety and operational continuity, while communications staff refined their processes for stakeholder notifications and crisis messaging.

However, important gaps emerged from other key leaders not participating. Their absence highlighted vulnerabilities related to compliance considerations, impact on teaching activities, financial response planning, and insurance coverage. Recognizing these issues, the university planned to include these leaders in future drills.

Universities must balance realistic drill scenarios and the potential stress or disruption to day-to-day operations. By keeping the scenario scope small, like a ransomware attack targeting student information systems, participants can concentrate on their specific roles without feeling overwhelmed.

Providing context and background information helps participants navigate the potential impacts. Scenario packets with incident descriptions, relevant technical explanations, and realistic timelines help guide discussions and reduce confusion.

Time-boxing each stage of the exercise, such as reserving 90 minutes with clear intervals for discussion, keeps the drill focused, efficient, and respectful of participants’ schedules.

Although cyber threats evolve, certain scenarios remain relevant for higher education.

A robust cyber drill program doesn’t have to break the bank. Universities can leverage existing resources by integrating drills into emergency management frameworks they already have in place. Trained law enforcement incident commanders, for example, can facilitate cyber drills without incurring extra costs.

Cross-training IT and security staff in broader incident command concepts also improves internal capacity to conduct drills. Short, focused exercises of 60 to 90 minutes can scale in complexity as the institution’s preparedness matures.

Free public resources like FEMA’s Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program guidelines (https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/national-preparedness/exercises/hseep) or EDUCAUSE tabletop exercise templates (https://library.educause.edu/resources/2021/4/cybersecurity-tabletop-exercise-toolkit) provide helpful frameworks for low-cost implementation.

Remaining agile in the face of emerging threats—like AI-powered cyberattacks—is crucial. These attacks leverage automation and machine learning to speed up and scale existing tactics, rather than introducing new methods.

Drills should include situations that challenge the institution’s capacity for handling large-scale threats, swift adaptation, and escalating complexity. A brief educational component can help participants distinguish between hype and real-world AI-driven risks.

Long-term success of cyber drill programs is best gauged through structured post-incident reviews of actual cybersecurity events. By comparing real incidents against drill scenarios, universities can pinpoint what worked, what didn’t, and how well the training translated to a genuine response.

For instance, if a university experiences a phishing incident resulting in compromised student data, reviewing whether IT staff recognized warning signs and escalated to security shows the tangible value of prior drills. According to IBM’s research, organizations that conduct post-incident evaluations reduce both response time and financial losses (https://www.ibm.com/reports/data-breach).

Over time, this feedback loop drives continuous improvement, solidifying cybersecurity posture and institutional resilience.

Cyber drills are far more than technical exercises or box-checking compliance activities. They are strategic investments in institutional resilience, cross-departmental coordination, and organizational readiness. By integrating well-structured cyber drills into their ongoing operations, universities evolve from reactive, siloed responses to proactive, unified defense strategies.

The return on investment becomes clear not just in improved response times or reduced downtime, but in the institution’s enhanced ability to protect its educational mission, research integrity, and community trust under sophisticated cyber threats. As higher education faces relentless cybersecurity challenges, institutions that commit to regular cyber drills will find themselves better equipped to navigate the inevitable, rather than hoping to avoid it.

Start Your 30‑Day Diagnostic - $399

Build a data‑informed, board‑ready cybersecurity plan in 30 days.

Includes expert guidance, 30‑day access to the Cyber Heat Map® platform, and weekly group strategy sessions.

No long‑term commitment. Just results.

Secure your seat today.