Chris Schreiber

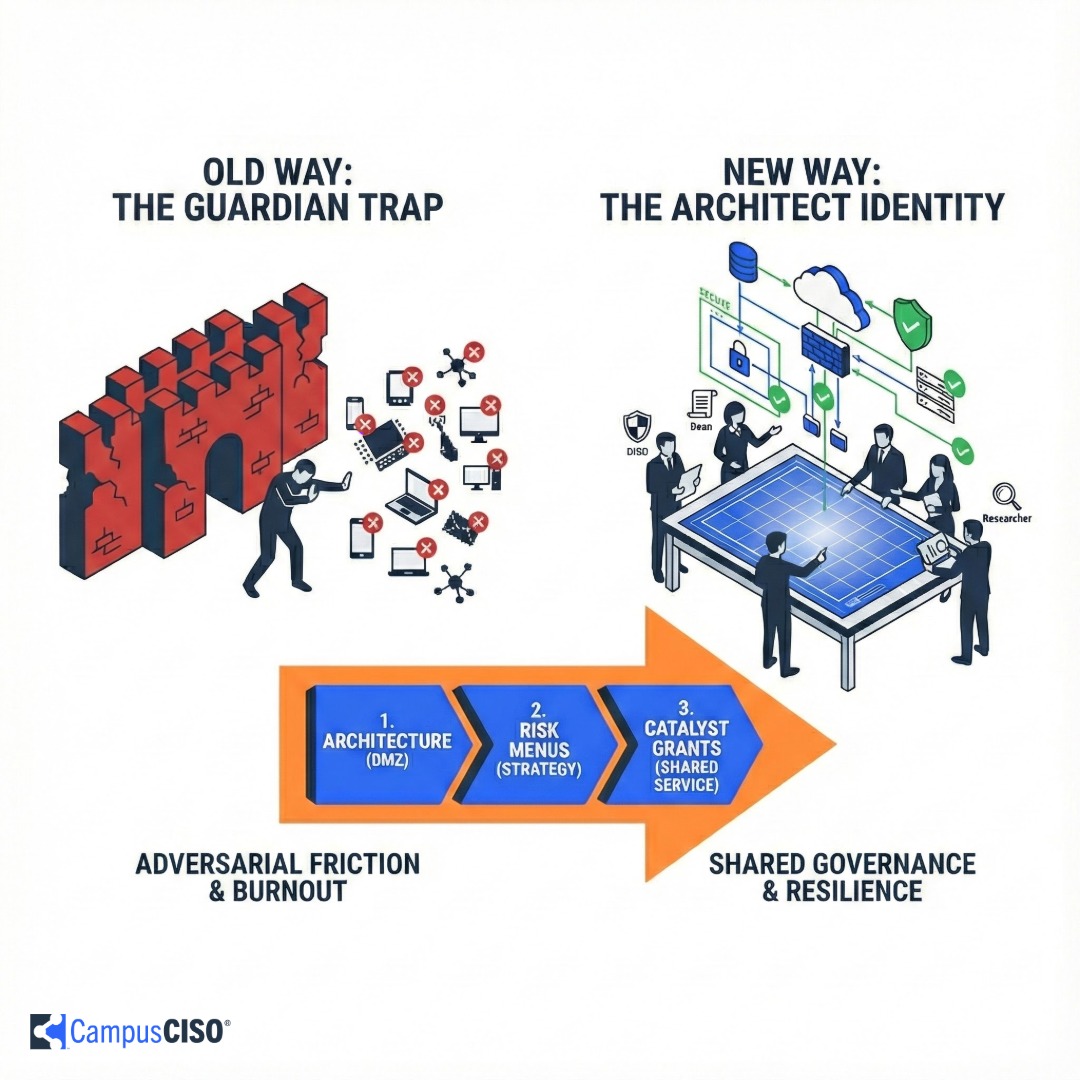

Higher education CISOs are burning out trying to enforce centralized compliance in decentralized environments where they lack direct authority. To thrive, security leaders must shift from an adversarial "Guardian" identity to a strategic "Architect" role that focuses on designing resilient environments rather than policing users. This article outlines practical force multipliers—such as translating technical risks into business pricing menus and utilizing catalyst grant models—to shift liability to campus executives and position security as a critical research enabler.

You can't centralize what was never meant to be centralized, and trying will turn you into the obstacle instead of the partner.

Only 22.9% of Research 1 universities describe their IT as highly centralized. At most major research institutions, you lack direct authority over the infrastructure you're expected to protect as CISO.

This isn't a problem to solve. It's the reality you chose to work in.

The traditional CISO playbook assumes a single chain of command where you can mandate controls. But you're not running a corporation. You're operating in a federation where distributed IT units support high-value research, and academic freedom isn't just philosophy. It's operational reality.

Friction occurs when you fight for control. You'll never win, and you become the “Department of No.” The CISO’s office becomes the obstacle, not the partner.

EDUCAUSE now ranks Collaborative Cybersecurity as the #1 IT Issue for 2026. The shift away from centralized enforcement is happening.

The question isn't whether distributed IT will go away. It won't. The question is whether you'll keep fighting it or start working with it.

Here's how the adversarial dynamic plays out.

Your vulnerability scanner flags a critical CVE on the controller PC for a grant-funded electron microscope. You require patching it within 30 days to meet policy.

The researcher explains the vendor certified the device only for Windows 7 with that specific set of patch levels. Adding new patches voids the warranty and potentially corrupts calibration data, rendering a $2 million asset useless.

You dig in. Policy is policy. The researcher escalates to the dean or vice president for research.

Then comes a consequence you didn't see: The researcher doesn't patch the machine. Instead, they buy a commercial 5G hotspot with grant money to bypass your network entirely. Now, that vulnerable machine is still operating, but it's completely invisible to your monitoring tools.

This isn't an edge case. 69% of IT leaders estimate at least half the devices on their networks are unmanaged—a challenge magnified in higher education's uniquely open environments. Force a binary choice between compliance and mission, and mission wins every time.

This results in Shadow IT: users constructing their own unmonitored infrastructure to escape your governance.

The peer architect approaches this differently.

You can't fix the vulnerability on the device, so you fix the surrounding environment. Leave the device unpatched, but the researcher places it in a Research DMZ (a segmented network your team monitors heavily, with no outbound internet access).

You trade perfect compliance for managed risk.

This requires a difficult ego check. You have to admit that the university's mission to create knowledge is more important than your policy to patch servers. You stop defining success as 100% compliance and start defining it as managed risk.

It also solves the resource trap. You cannot hire enough staff to police every lab. A majority of higher education cybersecurity professionals report that staffing issues have negatively impacted services at their institutions, and more than half don't believe they can successfully hire into existing positions. By shifting to an advisory role, you stop fighting a losing war of attrition and start designing architecture that survives human behavior.

The friction between auditors and researchers is the single biggest drain on your leadership capital.

Compliance teams spend a significant portion of their year managing audits. That operational capacity goes toward proving you're safe instead of actually making things safer.

The tension exists because you and the auditor are playing different games. The auditor is wired to check a box. You're wired to manage risk.

Your role as a risk advisor is to be the shock absorber between these two worlds. You translate the auditor's "Control Failure" into a "Risk Acceptance" a dean can understand and sign.

Here's how that conversation works.

You walk into the dean's office and present a resource trade-off: "We have a conflict between the audit requirement and your research timeline. The auditor wants this microscope patched, which we know voids your warranty and halts the grant. We can't do that, but we also can't leave it wide open and risk harm to the university. So we’ve designed Option C: We wrap the device in a secure enclave. It requires zero downtime for your team, but it means your researchers will need to use a jump-box to extract data. I need your signature here, not to waive the rule, but to approve Option C as our risk management strategy."

This approach solves the education gap. You aren't lecturing them about CVEs. You're giving them a menu of business outcomes.

It also addresses the audit pushback. Your signature on the same document validates that you believe the compensating control is sufficient. You use your authority to shield the researcher from the auditor.

This translation skill remains one of the most critical gaps for security leaders. When security teams speak in technical terms without business context, executives struggle to determine actual risk exposure.

By framing the decision as mission preservation rather than policy exception, you turn a compliance fight into a governance win.

How Risk Moves Off Your Desk:

The language matters more than you think.

I watched CISOs sign "Policy Exceptions" for years. When a breach inevitably happened on those excepted systems, the narrative was always: "Security gave them permission to be insecure." The CISO owned the liability because they signed the exception.

I realized that as a CISO, I had the authority to identify risk, but I lacked the assets to accept it. I didn't own the microscope, the grant, or the department’s research reputation. Therefore, I couldn't sign off on the danger.

The language shift to "Risk Management Strategy" forced the liability back where it belonged: with the business owner.

"Exception" implies we're breaking a rule. My fault for letting you.

"Strategy" implies we're making a resource decision. Your choice to fund the risk.

You have to engage the dean or vice president. You cannot have a risk acceptance conversation with a system administrator or a lab manager. They don't hold the checkbook.

Unfortunately, many higher education security leaders are stuck too low on the org chart to have that conversation effectively.

That gap exists because we keep bringing them exceptions instead of strategies. When you change the language, you earn the right to have the conversation at the budget level.

To escape the Guardian Trap, you must trade the hero's cape for an architect's pencil.

A dangerous misconception in our industry is that the CISO is the institution's shield. That identity leads directly to burnout because it creates an impossible standard of infallibility. In fact, 66% of CISOs report facing excessive expectations, and 63% say they have experienced or witnessed burnout within the past year.

The fix requires a shift in professional identity. You are not the Guardian. You're the Architect.

Picture a client who wants a wide-open floor plan that removes a load-bearing wall. An architect doesn't just sign off on the risk of the roof collapsing because the client really wants the open space. Instead, they present a menu of engineering options: install a steel support beam (high cost), change the layout (operational change), or abandon the renovation.

The client selects the option, and the client signs the plans.

As a cybersecurity leader, adopt the same rigor. When a dean demands an unsafe configuration, you don't grant an exception. You present the support column options—compensating controls, segmentation, or insurance. By forcing the business owner to select from a menu of priced options, you move the liability from your shoulders to the institution's risk register, where it belongs.

The pricing conversation succeeds when you convert abstract risk into operational currency.

You don't need a complex actuarial table. You need a three-item menu scoped like a kitchen renovation.

Sit down with the department's local IT director, not to fight, but to estimate. Together, you build the menu for the dean.

Option A (The Code Fix): We patch the system.

Price: $0 in software, but voided warranty and potential recalibration.

Operational Cost: Potential 2–4 weeks of downtime if the software breaks.

Option B (The Architect Fix): We build the Research DMZ (Network Segmentation).

Price: $2,500 for a dedicated firewall and 10 hours of network engineering time.

Operational Cost: Zero downtime. Researchers work effectively in a clean room.

Option C (The Do Nothing Risk): We sign the acceptance.

Price: $3.86 million (what higher education data breaches cost on average).

Operational Cost: Minimum 24 days to recover, with full recovery taking months to years.

Present these three options, and the math speaks for itself. Option A is operationally expensive. Option C is existentially expensive. This makes Option B, the architectural control, the rational business choice.

You aren't forcing them to be secure. You're showing them that Option B is the cheapest way to buy down their risk.

This isn't a technical build. It's a financial pilot.

You do not build the enclave first. You find the Catalyst Grant: that one high-profile research proposal on the dean's desk that cannot be awarded unless it meets strict new compliance standards (like CMMC Level 2 or NIST 800-171).

The CISO's move is to bring this opportunity to the CIO and make the case for a centralized shared service: "We're about to see five departments each hire their own compliance admin and build isolated, expensive solutions. If central IT stands up a Compliance Enclave as a shared service, we become the research enabler instead of the bottleneck. My team handles the security architecture and monitoring; your team owns the service delivery. You pitch it to the VPR as a cost-effective way to support compliant research."

This model works because it aligns incentives. 2025 data from UC San Diego's Regulated Research Cybersecurity Program shows exactly this pattern: centralized compliance advisory and compliant research enclaves are offered as a service to PIs, often subsidized so every lab doesn't need to reinvent the wheel.

The CIO asks for a reallocation of grant overhead funding. The CISO provides the compliance expertise and security architecture.

This creates the governance structure you want: the VPR becomes the bank, the researchers become the clients, and central IT becomes the service provider. Security moves from being an unfunded mandate to an embedded partner in research enablement.

These three force multipliers only work if you have the relationships to deploy them. The prerequisite for that estimation meeting is social capital.

You cannot surge trust during a crisis or a complex negotiation. You have to bank it beforehand.

This is why the peer architect model demands that you operate as an executive, not a technician. If you only show up when there's a firewall to install or an incident to remediate, you're a vendor, not a partner.

To build this capital, you must leave your security bubble and learn the business of the university (grant cycles, tenure pressures, and student enrollment cliffs) as well as you understand your SIEM.

Recent 2025 analysis on the CISO-to-CIO Pipeline confirms that the most effective security leaders are those who act as Trusted Advisors and Relationship Builders first, translating technical risk into institutional strategy.

In practice, you schedule discovery meetings with deans and directors with zero security agenda. Ask what their top three strategic goals are for the year and what friction is stopping them from hitting them.

Once you know a dean is worried about losing grant funding, your security controls become grant preservation tools. That shared context turns the architect conversation from an adversarial blockage into a collaborative problem-solving session.

The radical nature of these meetings isn't about the content. It's about the structural resistance you have to overcome just to get on the calendar.

The internal resistance often stems from a lack of executive standing. In higher education, rank dictates access.

This creates the chicken-and-egg trap. While the corporate world is elevating the role, with 48% of global CISOs now reporting outside the technology function to gain independence, higher education lags behind. In many universities, even the CIO reports to the CFO or Provost, effectively burying the CISO three layers down in the org chart.

Because the role is buried under IT, experienced executive CISOs often avoid higher education. Institutions then hire technical managers who lack the persona to command a room of deans, reinforcing the belief that the CISO belongs in the server room, not the boardroom.

You solve this by treating your limited access as a high-stakes design charrette, not a status report.

If the CIO manages these relationships rather than the CISO, you might only get one hour a year with the deans. Do not waste it reporting on phishing metrics. Use that hour to position yourself as the Architect of Resilience.

Ask: "If you lost your research data tomorrow, what project could end your career?"

That question cuts through everything else. It proves you are there to protect their mission, not just their computers.

CISOs consistently underestimate that soft skills are the hardest currency in the market.

Many technical leaders view networking as schmoozing, an optional layer on top of the real work. They assume that if their technical controls are sound, their authority will follow.

The data proves the exact opposite. 2025 research reveals a massive divide in the CISO market. Strategic CISOs (those who excel at C-suite engagement, relationship building, and business alignment) now earn 57% more than their technical peers.

This salary gap exists because the skill set is incredibly rare. The same report found that while 50% of CISOs are stuck in the Functional tier (good at tech, okay at influence), only 28% have successfully made the leap to Strategic.

The transition is difficult because it requires you to stop reporting and start building alliances. You aren't just pitching a security program. You are positioning yourself as a peer to the Dean of Medicine or the VP of Research.

If you don't have a network of campus leaders who trust you before a crisis hits, you're stuck cleaning up the mess. But if you do, you aren't just the CISO. You're the architect of the institution's cyber resilience.

Start Your 30‑Day Diagnostic - $399

Build a data‑informed, board‑ready cybersecurity plan in 30 days.

Includes expert guidance, 30‑day access to the Cyber Heat Map® platform, and weekly group strategy sessions.

No long‑term commitment. Just results.

Secure your seat today.